Tangzhong is an Asian technique where some of the flour and liquid from a bread recipe are cooked over the stovetop until thickened, then cooled before being added to the dough. But why? Before I understood tangzhong or its effects on bread, I could not understand why anyone might want to take this extra step. In this post, I discuss the ins and outs of tangzhong; including: what it is, why and when you might want to use it, and how to add it to your bread.

What Is Tangzhong?

Tangzhong is a technique derived from Asia, used in bread making, where some of the flour is cooked with a liquid, usually milk or water. This water roux gelatinizes the starches in the flour, and, when added to the recipe, produces a bread that is soft, fluffy, and moist with a good shelf life.

Tangzhong In A Nutshell

How Does Tangzhong Work In A Recipe?

Tangzhong works by creating a gel-like mixture that helps improve the texture and moisture retention of bread. The key science behind tangzhong lies in the gelatinization of starches present in the flour. When precooked, the flour is able to to soak in and retain more moisture, almost by double. This results in a bread that stays fresh for much longer (does not go stale as quickly), and is more soft and tender than a bread made without tangzhong.

A Breakdown Of The Science Of Tangzhong

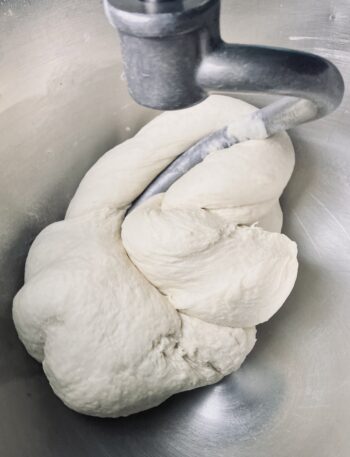

When the flour and liquid mixture (tangzhong) is heated, the starches in the flour absorb water and gelatinize, which involves the swelling and thickening of starch granules. The gelatinized starches form a network or matrix within the tangzhong, which can hold onto water and create a structure that helps trap moisture during baking. This extra water retention contributes to a softer and moister crumb in the finished bread.

When the tangzhong is added to bread dough, the gelatinized starches help to enhance the dough’s structure, resulting in a more stable and uniform rise during fermentation and baking. It also delays the retrogradation of the starches (the process where the starches in bread recrystallize and firm up), keeping the bread from staling and helping the bread to stay softer and fresher for a more extended period of time. This improved moisture retention and delayed staling contributes to a longer shelf life for the bread.

What Kinds Of Recipes Pair Well With Tangzhong?

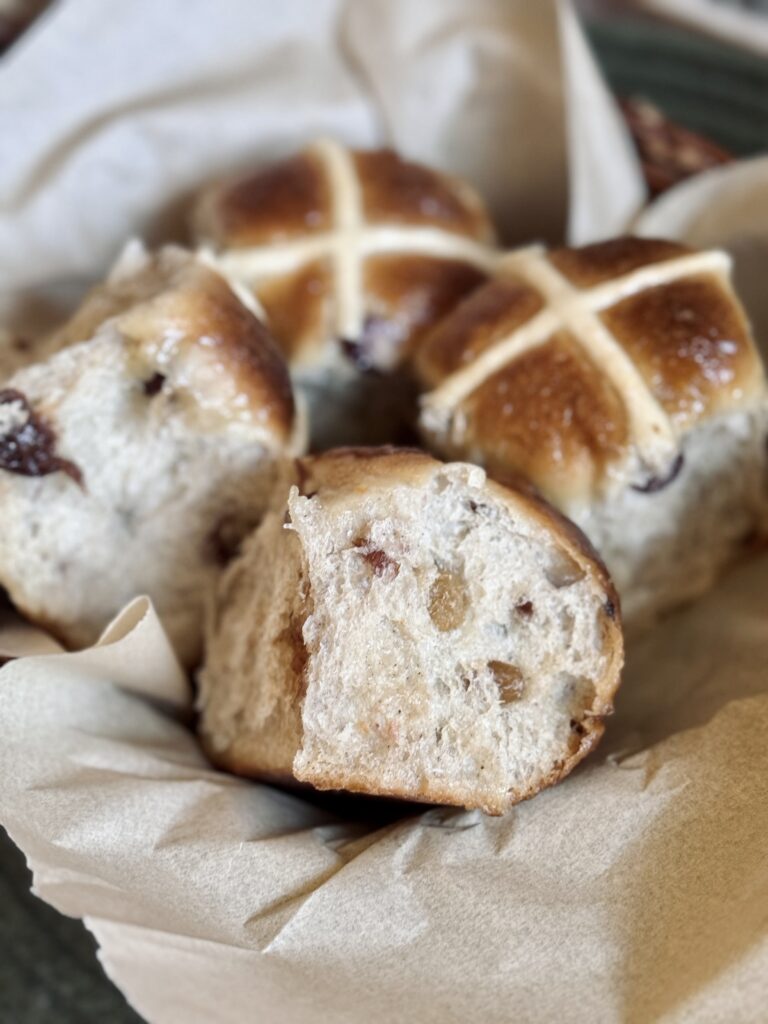

Tangzhong goes well with any bread where a soft and tender crumb is desired. This usually includes milk-based breads or breads made from stiff doughs. Tangzhong pairs well with sweet breads, such as cinnamon rolls or pull-apart bread, but also makes the perfect addition to soft and savory breads like sandwich bread and any kind of bun (ex – dinner rolls, hamburger/hot dog buns). Tangzhong would not pair well with artisanal breads, such as baguettes or country bread, where a chewy crust and open interior are desired.

How Do I Make Tangzhong?

Making tangzhong is easy.

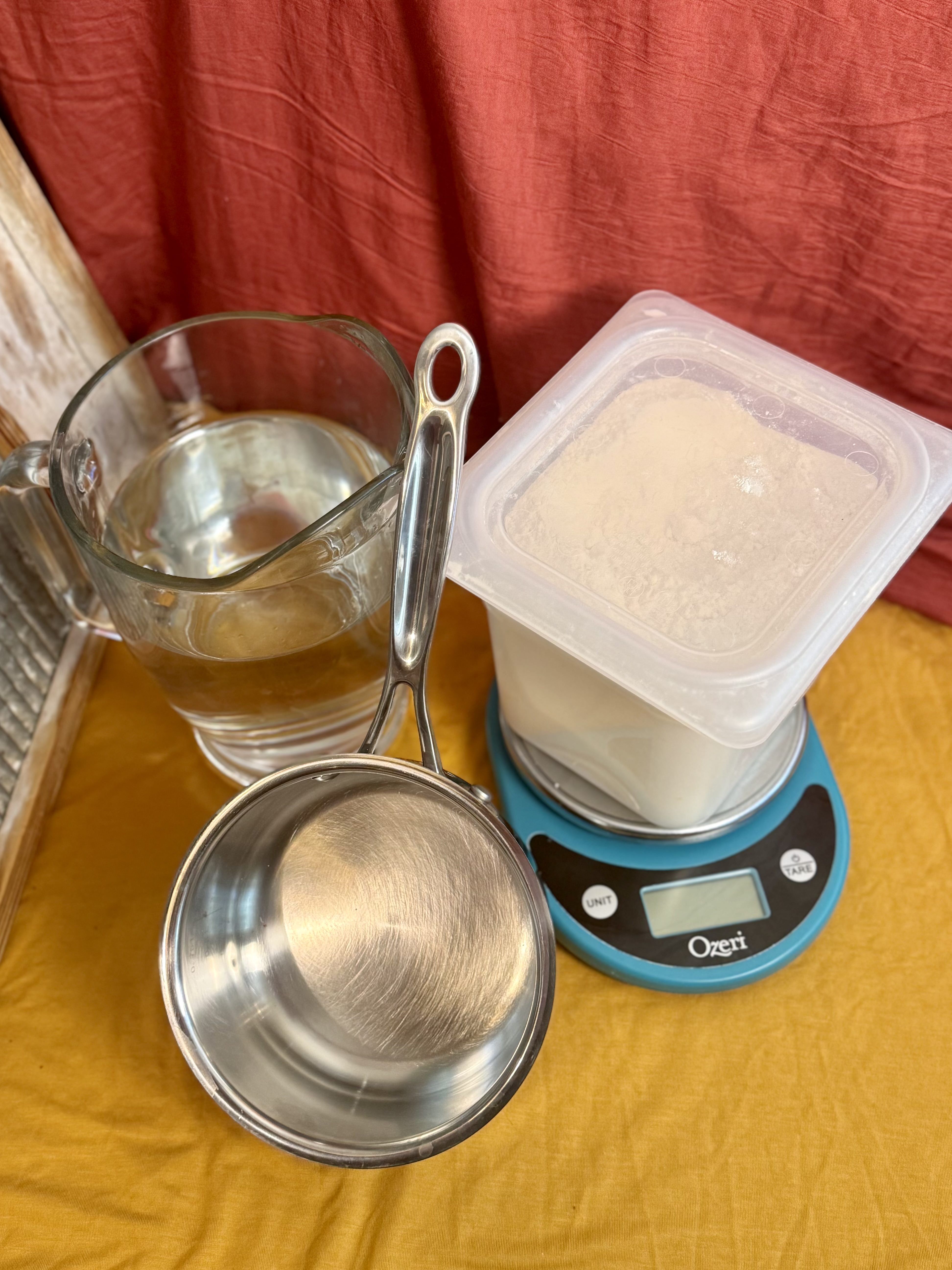

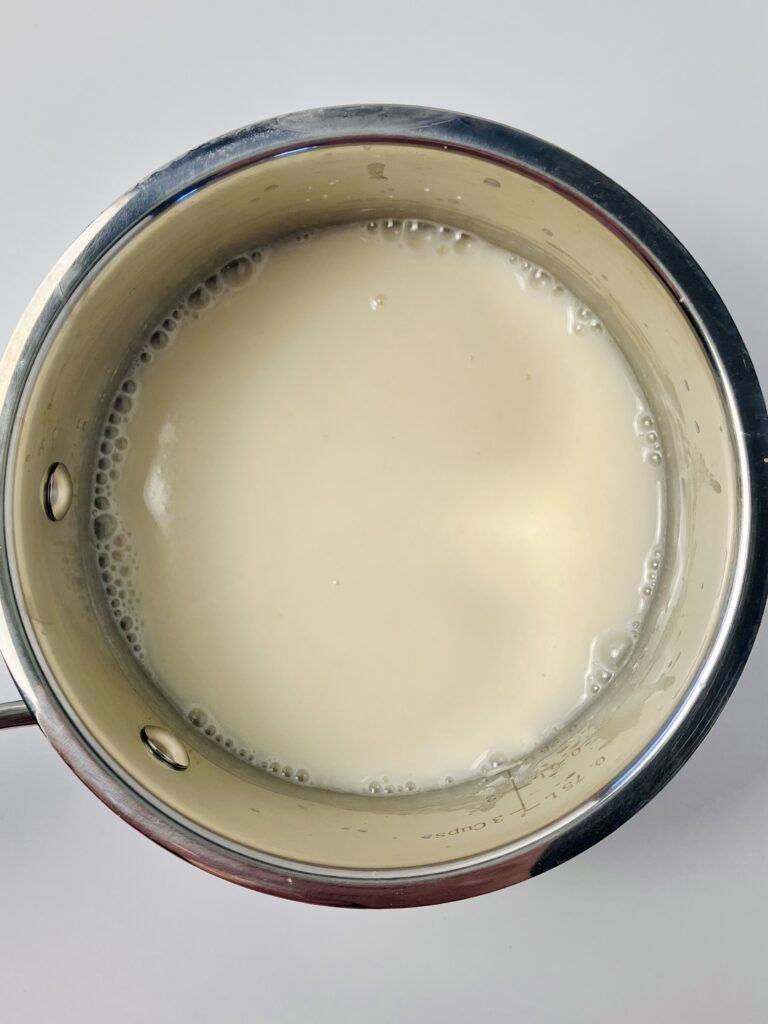

Start by whisking together five parts liquid (generally water or milk) to one part bread or all-purpose flour in a small saucepan until no lumps remain. For example, if you use 100 g of liquid, you will need 20 g of flour.

Place the saucepan over medium heat and whisk continuously until the mixture thickens and transforms into a gel-like consistency.

Remove the tangzhong from heat and cover tightly with plastic wrap (this is to prevent a skin from forming on the outer layer). Let it cool to room temperature before incorporating in your bread recipe.

When Is The Best Time To Make Tangzhong?

A tangzhong can be made anytime before you begin mixing your bread dough. This means you can make it the morning or evening you mix your bread, as long as it has ample time to cool. You could place it in the refrigerator or freezer to speed along the cooling process.

In most recipes where I use tangzhong, I also use a sweet stiff starter. In this case, I like to make the tangzhong when I mix the starter, then let the tangzhong cool in the refrigerator while the starter rises.

I also sometimes make the tangzhong right before I mix my dough. In this case, I make the tangzhong first, before I prepare/measure any other ingredients. Then, I place the tangzhong in the freezer while I prep my dough. To make sure the tangzhong is cool enough, I stick my finger into the center. If it is warm, but does not burn my finger, it is fine to incorporate into the dough.

What Kind Of Flour Or Liquid Can Be Used To Make Tangzhong?

Tangzhong can be made using any kind of flour with sufficient starches and most liquids that can be cooked on the stovetop. I usually stick to white flour, bread or all-purpose, but like to play around with the liquids. I have made tangzhong using water, milk, buttermilk, and even pineapple juice. Let’s take a closer look at the possibilities for each:

As far as flour goes, any flour with sufficient starches will work. I have only tested tangzhong with wheat flours (white flour – bread and all-purpose – and whole wheat); though, any kind of wheat flour should work. This includes: whole wheat, spelt, rye, semolina, etc. You may notice that some flours absorb a lot more liquid than others, thereby creating a thicker tangzhong. The recipe developer should account for this and make adjustments to the recipe-specific tangzhong formula.

I have had many ask me if gluten-free flours will work for tangzhong. I have not tested gluten-free options in tangzhong, but I imagine starchy gluten-free grains would work. Starches like potato starch, tapioca starch, and corn starch will work to thicken the liquid (noting the proportions may need to be adjusted [since this is straight starch and not flour]), but I am not sure if they would have the same effect in the bread.

As far as the liquid goes, you can use almost anything. Water is common. Any kind of milk will work: whole milk, two percent, low fat, lactose-free, or even coconut, almond, soy, etc. I’ve also used buttermilk and pineapple juice with great success. I generally use whatever liquid makes sense with the recipe, or is already part of the recipe.

Once you understand tangzhong, how to make it, and its effects on the dough, there is a lot of flexibility that can occur within the ingredients, depending on your personal recipe goals.

How Do I Convert A Bread Recipe To Tangzhong?

First, consider if tangzhong would really pair well with the recipe. Remember – soft and tender breads, like milk breads or breads made from stiff doughs – pair well with tangzhong. Recipes that are meant to have a chewier texture, like country bread or pizza crust, are not good options for tangzhong. If you are struggling with these breads, it is likely another issue, and tangzhong will not fix the problem.

Second, make sure you know at least the amount of flour and water you are using by weight (not volume!). One cup of water weighs twice as much as one cup of flour, so this formula will not work for volume measurements.

Next, it is important to consider the hydration (how wet or dry the dough is) of the recipe. Since the tangzhong’s addition allows more moisture to be absorbed, it is important that the hydration of the original recipe be at least 75% before converting to tangzhong. Otherwise, the resulting dough may be too thick and dry. I say “may” because I have converted several stiff doughs to tangzhong and ended up reducing the amount of liquid I added to the formula back down to keep the consistency I was going for. When experimenting, it is best to hold back some of the added liquid when mixing the dough. This way, if your dough does not need the extra liquid, the proportions of the recipe (rest of the ingredients) are not thrown off.

To calculate hydration, simply divide the total amount of liquid by the total amount of flour. Read more about hydration here. Essentially, there is a simple way and a technical way to calculate hydration. For the sake of simplicity, it is okay to exclude ingredients like eggs or even your sourdough starter that contain extra water or flour content. The rough estimate given by simply dividing the amount of water by flour in the recipe is good enough.

If the total comes out to at least .75 (75%) you are good to go. If the total is less than this, you will need to adjust the amounts of flour and liquid in the recipe to get the desired hydration of 75%. Here’s how to do that:

Let’s say the recipe calls for 315 g of water and 525 g of flour. 315 divided by 525 is .60 (60%). So, the dough’s current hydration is 60%, and we need it to be at least 75%. To fix this, we will need to add more liquid. We can calculate the specific amount of liquid needed by taking the amount of flour in the recipe (in this case, 525 g) and multiplying it by .75 (75%). 525 multiplied by .75 gives us 393.75 g of liquid that we need to add to the recipe. It is okay to round this number up to 395, or even 400, grams of liquid. In conclusion, the new totals of water and flour for this recipe are 395 g of water and 525 g of flour. Now this recipe is ready to convert to tangzhong.

A standard slurry of tangzhong uses 5-10% of the total weight of the flour and consists of five parts liquid to one part flour (by weight). Let’s continue with the totals above to determine how much flour and water is needed to make our slurry.

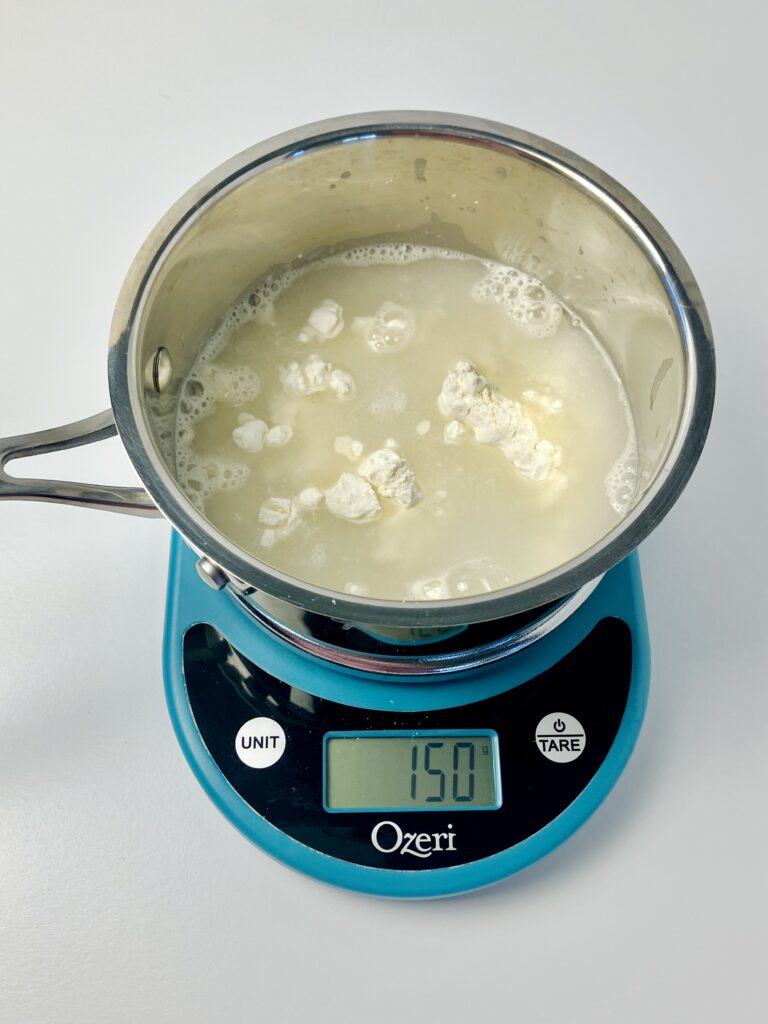

To start out, use 5% of the total weight of the flour. The higher the percentage of tangzhong in the recipe, the more soft and plush the dough is. 10% can be quite a lot to start with; always start with the lower amount and increase as desired. 5% of 525 g of flour is calculated by multiplying 525 X .05 (5%). The end result is 26.25 g. I am going to round this up to 30 g of flour for my recipe. Since this still falls in the 5-10% range, this is not an issue. Now, I know I need 30 g of flour, but how much water should be used to create the tangzhong? Since a tangzhong consists of one part flour to five parts liquid, I am going to multiply 30 by 5. 30 X 5 = 150 g of liquid. In conclusion, I will make the tangzhong by whisking together 30 g of flour with 150 g of water until no lumps remain, then heating over medium heat and whisking continuously until a gel-like paste forms. Last, I will remove from heat, cover tightly to prevent a skin from forming, and let it cool to at least room temperature before incorporating into my recipe.

Finally, we need to adjust the amounts of water and flour in the recipe. Since we used 30 g of flour to make the tangzhong, we will subtract this from the original 525 g of flour in the recipe. 525 – 30 = 495 g of flour. Repeat this process with the liquid in the recipe. 395 -150 = 245 g of water. Now, we can make the recipe using our new totals of flour and water and incorporating the tangzhong.

To review, the original totals of flour and water for this example were as follows:

- 525 g of flour

- 315 g of water

This gave us a hydration of 60% (calculated by dividing water by flour) which is too low of a hydration to add a tangzhong. So we increased the hydration to 75% by adding more liquid. The exact amount was determined by taking 75% of the flour in the recipe. The new totals were as follows:

- 525 g flour

- 395 g water

Now, we took a portion of this flour and water and made a tangzhong. A tangzhong consists of 5-10% of the total flour, and is generally one part flour to five parts liquid. Our tangzhong totals were as follows:

- 30 g flour

- 150 g water

Then, we subtracted these amounts from the flour and water in the recipe, so that we could add in the tangzhong. The final totals were:

- 495 g flour

- 245 g water

- Add tangzhong to the dough

And, that’s it! Remember: if you had to increase the amount of liquid in the recipe, it is a good idea to hold some of it back during mixing, adding as needed to get the consistency you are going for. Once the tangzhong is incorporated into the dough, you can follow the recipe directions as written.

Now you know how to convert any recipe to tangzhong!