A sweet stiff starter is a type of sourdough starter used to reduce sour flavor in bread. But, how can it do this? And, why would a sour flavor even need to be eliminated? In this post, I discuss the ins and outs of sweet stiff starter; including: what it is, why and when you might want to use it, how to make it, and more.

A Brief Summary Of Sweet Stiff Starter

- Sweet stiff starter is a low hydration starter, meaning it contains more flour than water. This provides more food for the yeast to feed on, and less water for bacteria to thrive in, which means reduced chances of your starter becoming sour.

- Sweet stiff starter contains a very specific percentage of sugar (10-15%). This is enough to create osmotic stress, which is the goal. This percentage is not so much that it kills the yeast, but not so little that fermentation speeds are increased.

- The purpose of creating osmotic stress is to limit bacteria cell regeneration. This means the bacteria that create acids (sour flavor) are not reproducing as rapidly.

- A sweet stiff starter will only work if your process also works. Fermentation is key. Ferment the starter in temperatures that favor yeast reproduction for the most success (70-75 F; 21-24 C).

- Sweet stiff starters are most commonly paired with enriched doughs, though they can also be found in doughs that are “sweet” and “stiff” themselves.

What Is A Sweet Stiff Starter?

A sweet stiff starter is a type of starter that is low in hydration (more flour than water) and contains a percentage of sugar. The overall goal of a sweet stiff starter is to limit acidity from bacteria and favor yeast reproduction in order to reduce sourness.

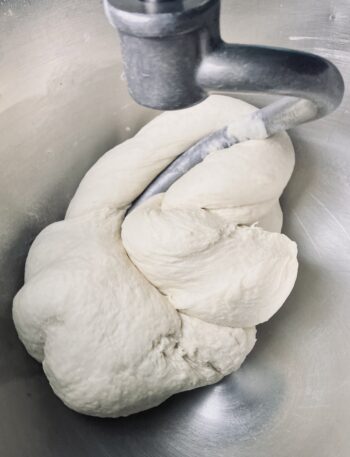

To make the starter “stiff,” the hydration should be less than 65%, meaning it is like a dough ball and may require kneading. The “stiff” aspect of a sweet stiff starter favors yeast in that it gives them more food to continue feasting on, while also limiting bacteria (who thrive in wet climates) with the use of less water.

The amount of sugar present in a sweet stiff starter is very specific, 10-15% of the total flour. This specific percentage of sugar works to create something called “osmotic stress,” which, in a sense, suffocates/slows the ability of bacteria to reproduce. Having less bacteria results in less acidity (aka – sour flavor) in your starter.

What Is The Difference Between A Liquid Starter And A Stiff Starter?

The true definition of a liquid starter is going to depend on who you ask. Some define a liquid starter as a starter with more water than flour, as opposed to a stiff starter, which contains more flour than water. However, I have never used a sourdough starter with a hydration greater than 100%; therefore, you will find me using the terms “liquid starter” and “100% hydration starter” interchangeably. A 100% hydration starter (liquid starter by my book) is made up of equal parts flour and water by weight. This kind of starter is easily stirred with a spoon and has the consistency of a thick paste. It is also easily dissolved into water and incorporated into bread dough.

Stiff starters, on the other hand, cannot be stirred with a spoon. They are generally maintained around 50% hydration, sometimes less, meaning the starter contains at least two parts flour to one part water by weight. The higher proportion of flour compared to water means stiff starters are generally kneaded to help incorporate all the flour. They appear and feel very similar to bread dough. Stiff starters do not incorporate as easily into bread dough as liquid starters do, and may need to be dissolved into (or softened by) water first.

Summary

While the true definitions vary from baker to baker, the definitions of “liquid” and “stiff” starters, as I reference them, are as follows:

- Liquid Starter: A liquid starter is a type of starter that is easily stirred with a spoon and has the consistency of a thick paste. An example is a 100% hydration starter, which consists of equal parts flour and water by weight.

- Stiff Starter: A stiff starter is a type of starter that contains more flour than water by weight and must be kneaded like bread dough. An example is a 50% hydration starter, which consists of two parts flour to one part water by weight.

What Is The Difference Between A Stiff Starter And A Sweet Stiff Starter?

The only difference between a stiff starter and a sweet stiff starter is sugar. Only the sweet stiff starter contains a percentage of sugar.

What Effect Does Sugar Have?

In essence, sugar slows down bacteria’s ability to reproduce.

To understand this, we must understand how our starter functions. Within your starter are both yeast and bacteria. Yeast feed on sugars (from the flour), releasing CO2 and ethanol in the process. Bacteria break down proteins in the flour, also releasing CO2 and ethanol, but in smaller quantities. In addition, bacteria release two types of acid: lactic and acetic. The acid, released by the bacteria, is what causes a sour flavor.

Now, this whole topic is very complex. It’s not like the bacteria, or the acids they release, are a “bad” thing. The problem is that the bacteria reproduce faster than the yeast, which can create an imbalance in your starter and in your dough. This is what can lead to overly sour bread or bread that “overproofs” before it is fully aerated. This is where sugar comes in.

What the sugar does is slow down the bacteria. It’s meant to sort of keep the bacteria in check with the yeast and restore balance, maybe even hinder them just a bit. The goal is to prevent or limit sourness coming from the acids they produce.

When sugar is added to sourdough starter and bread dough in small quantities (under 10%), it does not harm the bacteria. In fact, it his rather helpful. Small amounts of sugar kickstart the yeast, encouraging feeding and CO2 production, as well as bacterial growth. On the other end of the spectrum, if sugar is added in large quantities (over 15%), it can be harmful. Too much sugar steals water and dehydrates yeast cells. It can thoroughly stall out yeast and bacterial reproduction, potentially killing the starter altogether. A perfect balance is necessary. Added in just the right amount, though, (10-15%), sugar can have optimal effects on the bacteria without harming the yeast.

This happens in sweet stiff starter. When you add about 10-15% sugar to the starter, it creates something called “osmotic stress.” This stress stops the bacteria from multiplying as rapidly, which then limits the amount of acid buildup (since the bacteria aren’t reproducing as quickly).

In other words, the percentage of sugar added is very specific. It is enough to limit the rapid multiplying of bacteria, but not enough to completely kill the starter. Therefore, the starter still functions appropriately but the buildup of acid from the bacteria is limited, which reduces the sour flavor.

Summary

Adding sugar to your starter limits the ability of bacteria to reproduce, which contributes to a reduced sour flavor.

What Effect Does Fermentation Have?

Just like with anything bread-related, fermentation is key. It can make or break the effectiveness of a sweet stiff starter. Without proper fermentation, you can still end up with a sour starter and a sour bread, despite your efforts to prevent this by using a sweet stiff starter.

It is helpful to ferment the starter in an environment that favors yeast reproduction – around 70-75 F (21-24 C), though a number of variables can influence this. Too cold and acetic acid production is favored, resulting in a slower rise and more acetic acid production. Too warm and lactic acid production is favored, which is not as sour as acetic acid, but whose effects can still be noticed in bread.

A sweet stiff starter fermented for too long – no matter the temperature – will use up its food source and, of course, become sour again. Try to use the starter before it has “over proofed” (or, fallen from peak). This way, it will be less acidic.

For breads made with a sweet stiff starter, a warm bulk fermentation is ideal (in the 70-75 F [21-24 C] range), though the dough can be placed in the refrigerator for up to twelve hours without developing a noticeable sour twang.

Summary

Without proper fermentation, the starter can still result in sourness. Ferment your starter in temperatures that favor the yeast (70-75 F; 21-24 C) and use the starter at peak (not over) for best results.

The Science Behind Sweet Stiff Starter

To put it all together, here is the science behind a sweet stiff starter in a more straightforward way:

A sweet stiff starter is low in hydration, meaning it contains less water than flour. The increased amount of flour in a sweet stiff starter means more food for your starter, which consists of yeast and bacteria, to feed on. However, because the water is limited, bacteria reproduce slower than they would in a more free-flowing (wet) climate. This plays to your favor because bacteria produce acids that cause sourness.

To limit acid production even more, sugar is added to the starter. Adding 10-15% sugar is just the right amount to create osmotic stress (but not kill the starter), which further limits the ability of the bacteria to reproduce, reducing chances of acidity/sourness even more than with a stiff starter alone.

Because a sweet stiff starter takes all these measures to limit acidity, it would be classified as a type of starter that favors yeast growth over bacterial growth, which results in a milder “sour” flavor when maintained correctly.

Any starter that is maintained incorrectly can still become sour. If left to ferment too long, or if left to ferment in certain environmental conditions (such as a refrigerator, which encourages acetic acid production), the starter can still result in a final loaf that is “sour,” despite the use of additional flour to encourage yeast production and sugar to create osmotic stress.

How Do I Make A Sweet Stiff Starter?

To make a sweet stiff starter, you need to make a starter with a hydration of 50% (or less) that contains 10-15% sugar. These percentages are based in baker’s math, meaning they directly correlate to the total amount of flour in a recipe.

For example, to make a starter with 50% hydration, first determine how much flour you want to use. Let’s say I wanted to use 100 g of flour. 50% of 100 g is 50 g (100 X 0.5). Therefore, I would use 100 g of flour and 50 g of water to make the stiff starter at 50% hydration.

To add 10-15% sugar to the starter, I again need to consider the amount of flour I added. 10% of 100 g is 10 g (100 X 0.1). 15% of 100 g is 15 g (100 X 0.15). Therefore, for 100 g of flour, I need to use 10-15 g of sugar to create osmotic stress.

The amount of your regularly maintained starter that you use to build the sweet stiff starter is up to you. Using more seed means your sweet stiff starter will rise faster, but will also keep more of the bacteria carried over from your regularly maintained starter. Vice versa, using less seed means your sweet stiff starter will rise slower, but will not carry over as much bacteria from your regularly maintained starter. I like to keep the amount of seed equal to or less than the amount of water I add to the starter. Therefore, if I am using 50 g of water to hydrate the starter, I would use 50 g (or less) of my regularly maintained starter to inoculate the sweet stiff starter.

Once you have determined how much flour, water, sugar, and seed you will use to make the starter, weigh each ingredient and roughly mix everything together in a bowl. Using your hands, knead the mixture in the bowl or on the countertop until all of the ingredients are fully incorporated. Use more flour or lightly wet hands as necessary to manage your dough/starter. You can continue kneading the starter for up to five minutes (this is optional) to ensure the yeast from your seed are well distributed, encourage a more elastic (strong) gluten network (which will help your starter rise), and incorporate oxygen (which stimulates yeast growth). Last, transfer the starter to a container to rest (covered) at room temperature (70-75 F; 21-24 C) until doubled or tripled in size, 8-12 hours.

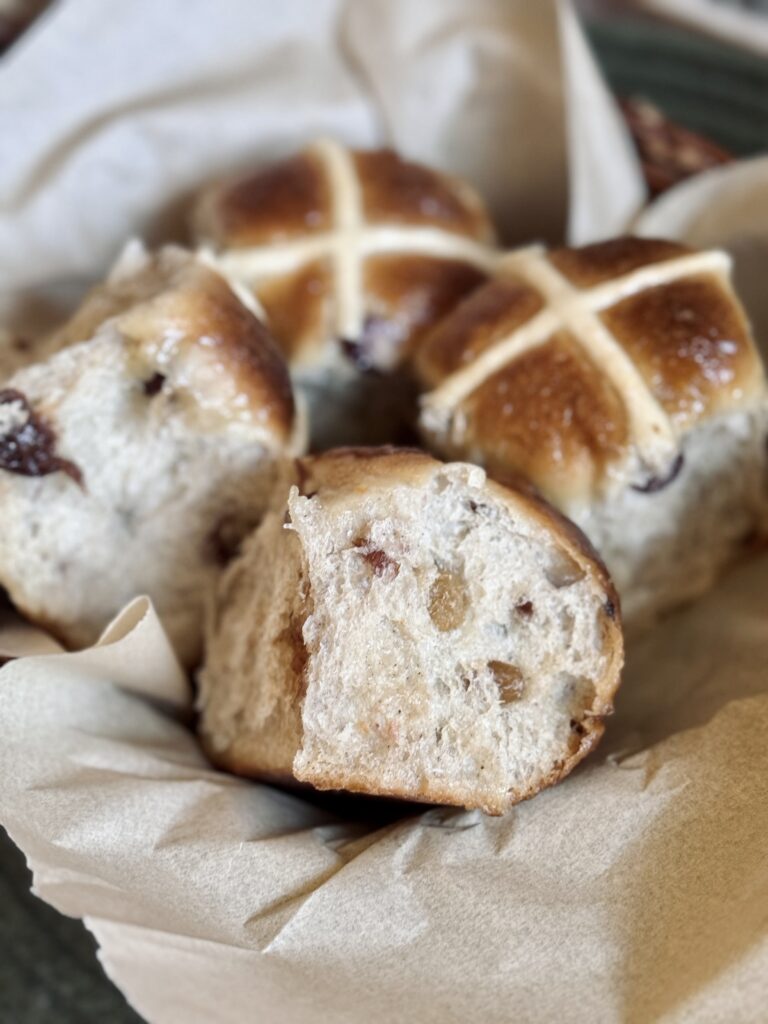

What Kind Of Bread Should I Pair With Sweet Stiff Starter?

While you can use a sweet stiff starter with anything you desire, sweet stiff starters are generally used side-by-side enriched doughs (doughs containing milk, butter, sugar, etc) or other stiff doughs where a reduced sour flavor is desired. Examples include: brioche (enriched), cinnamon rolls (enriched and sweet), bagels (stiff), etc.

Generally, recipes that include sweet stiff starter are “sweet” and/or “stiff” themselves, though not always. It is common for the attributes of the starter to be kept in the bread dough in order to keep a reduced sour flavor. Even savory recipes, like bagels, may contain a percentage of sugar whose purpose is not to sweeten, but to create osmotic stress and eliminate sourness.

It is not common to pair sweet stiff starter with high hydration (wet) rustic breads, such as baguettes, English muffins, or country bread. While it is possible, bacteria create more complex flavors that are generally desired in these types of breads. However, if you do not desire these flavors, you can include a sweet stiff starter in any recipe, noting that technique will need to be adjusted when making the dough.

Summary

Sweet stiff starters are most commonly paired with enriched doughs, though they can also be found in doughs that are “sweet” and “stiff” themselves.

Do I Have To Maintain A Sweet Stiff Starter In Addition To My Regular Starter?

It is not necessary to maintain a sweet stiff starter along side your regularly maintained starter. This is because you can build a sweet stiff starter from your regularly maintained starter any time you need one.

If you want to, though, you can! One fun thing about maintaining a sweet stiff starter is that the yeast in your starter can be trained to become osmotolerant – meaning they can efficiently leaven bread recipes where sugar content is high and they are under high osmotic concentrations.